STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- A helicopter camera has changed the way travelers will experience Angkor Wat and other Khmer temple-cities

- Consortium of archaeologists brought in to fill in the blank spaces on map of Angkor

- Locals hope discovery will inspire travelers to explore Siem Reap's lesser known Khmer ruins

Siem Reap, Cambodia (CNN) -- Visit Cambodia's number

one tourist attraction, Angkor Wat, with the average tour guide and

you'll probably leave the UNESCO World Heritage Site with your head

swimming in dates, dimensions and unpronounceable names of kings.

Jaya-who?

You might also get the

impression, as I did when I first visited two years ago, that the

magnificent temple complex you scrambled around in sweltering heat is

confined within its sturdy walls and scenic moat, and the city ended

there.

Turns out that's not the case.

A new report released by the U.S.-based National Academy of Sciences

(NAS) highlighting the results of an April 2012 airborne laser survey

-- the first of its kind in Asia, covering 370 square kilometers of

northwest Cambodia's Khmer Empire archaeological sites -- has revealed a

much grander Angkor landscape, one without parallel in the

pre-industrial world.

Even more sensational,

the June announcement of the findings confirmed the existence of a huge

medieval city buried beneath impenetrable jungle on a remote mountain.

Re-writing Cambodia's history books

Angkor was the capital of

the Khmer Empire, which was founded in 802 AD on Mount Kulen when

Jayavarman II was declared universal monarch.

These days the most

popular Angkor sites for tourists are Angkor Thom, which is home to

Bayon and its massive carved smiling faces; magnificent Angkor Wat; and

smaller temples such as Ta Prohm, Preah Khan, Pre Rup and Ta Nei.

Yellow indicates aerial surveys areas.

Yellow indicates aerial surveys areas.

But the precise data

gathered by LiDAR, a remote sensing laser instrument, reveals that

Angkor was actually a monumental, formally planned and low-density

mega-city.

Phnom Kulen, or Mount

Kulen, meanwhile, 48 kilometers north of Siem Reap, has been identified

as the location of the medieval city of Mahendraparvata, or the Mountain

of Indra -- King of the Gods.

This makes Angkor the

world's largest urban conurbation prior to Britain's 18th-century

Industrial Revolution -- a revelation that completely alters how experts

are looking at the area.

While the ancient urban

network's existence was mentioned in inscriptions and long suspected by

French archaeologists working in Cambodia, it couldn't be confirmed due

to the remoteness of ruins already discovered on the plateau, the

inaccessibility of much of the mountain and the existence of landmines

installed by the Khmer Rouge.

Dr. Damian Evans of the LiDAR mission uses a map to explain the monumental scale of the mega-city of Angkor.

One of the authors of the NAS report, Australian archaeologist Dr. Damian Evans, is director of the University of Sydney's Robert Christie Research Centre in Siem Reap and the chief architect behind the costly LiDAR mission.

He brought together

eight different archaeological organizations, including the Cambodian

government's APSARA Authority, which manages the region's archaeological

sites, to form the Khmer Archeology LiDAR Consortium, which raised funds for the project and shared data.

The LiDAR mission was

conceived to fill in the blank spaces on the map of Angkor, Evans says,

as we slip into the jungle just outside the walls of Angkor Wat.

"Nothing on the forest floor is random, not even a termite mound," Evans explains as he points out anthills.

"While a lot of the city

is buried beneath the ground, it impacts the surface in subtle ways.

The movements, activities and actions of these people hundreds of years

ago remain inscribed into the landscape.

"None of these lumps and

bumps and dips made any kind of sense, but once you see the LiDAR

imagery, it's strikingly evident that what you're looking at are the

remains of a city associated with Angkor Wat."

Using technology to speed things up

Out of the sight of the

one million tourists who visit the temple-city every year,

archaeologists are at work on excavation projects.

They use found remnants

of the region's rich Khmer history, culture and way of life to piece

together a story that's continually developing, changing visitors'

understanding and experience of Angkor in the process.

Archaeologists have

worked on the ground here since naturalist Henri Mouhot stumbled upon

Angkor Wat in 1860, excavating temple ruins deep within jungles for

visitors to tour, peeling away vines from palaces for us to explore and

unearthing riches to be displayed in museums.

For many archaeologists,

a discovery can represent a lifetime's work. The LiDAR technology

changes all that, speeding up the process.

"What LiDAR takes away

is a little of the Indiana Jones stuff of whacking through cactus,

spiders, thorny trees and mud puddles," says American archaeologist Dr.

Miriam Stark, onsite in Siem Reap.

"You can still have your

spiders, snakes and bugs, and all those rich experiences, but now you

know you're getting somewhere, which is a lot more satisfying."

A taste of that Indiana Jones stuff awaits our party at 492-meter-high Mount Kulen, a 90-minute drive from Siem Reap.

Near Preah Ang Thom,

home to a colossal 16th-century reclining Buddha carved out of solid

rock, my photographer husband and I swap our four-wheel-drive vehicle

for motorbikes, riding behind local guides for a daylong bone-rattling

exploration of the eight-kilometer-wide and 32-kilometer-long mountain

plateau.

We cling on tight as our

guides, familiar with every cave and cranny on the landmine-riddled

mountain, tackle muddy trails up hills, bump over log bridges, fly

through fast-flowing streams, get stuck in sludgy puddles and go

off-road, bouncing along jungle tracks only they can see, every now and

again alighting to slash away vines and branches with a scythe to create

our own paths.

We hike to see enormous

carved stone statues of an elephant and lions at Sras Damrei (Elephant

Pond) buried deep within the forest and scramble about the ruins of

Prasat Rong Chen, the three-tiered laterite temple where the Brahman

priest made Jayavarman II a god-king.

We emerge from thick jungle to gaze at the red brick temple of O Paong, grass and trees sprouting from its cracks.

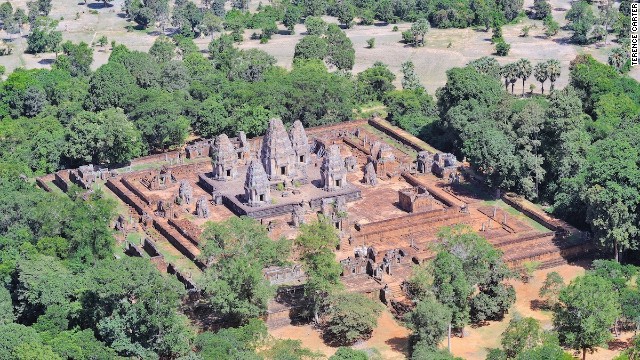

Angkor's splendid temple architecture.

Angkor's splendid temple architecture.

Another day we visit

beautiful Beng Mealea, taken captive by tangled roots and a forest that

grows within and around the moss-covered temple, and the remote,

sprawling Koh Ker, where temple after crumbling temple wait to be

explored.

We see a total of four tourists the whole day.

"Digging" for ruins in the air

We also board the

helicopter that was equipped with the LiDAR instrument to view the

area's splendid temple-cities and grasp the size of the colossal new

cityscape that's been recently uncovered.

From the air it's easier

to understand how challenging the archaeologists' job must have been

before the device bombarded the ground with laser beams -- a million

pulses every four seconds -- to record data that ultimately provided the

precise information that has forever changed how archaeologists work.

At a traditional Khmer

stilted house on Siem Reap's riverside that serves as the Robert

Christie Research Centre, I meet archeology professor Dr. Roland

Fletcher, co-director of the Greater Angkor Project.

"I like to explain it like this," begins Dr Fletcher.

"When you came here you

landed at the airport and thought of yourself as driving to Siem Reap,

then driving from Siem Reap to Angkor. But when you were at the airport

you were really 15 kilometers inside the Angkor city and Siem Reap is in

the suburbs of Angkor ... at Angkor Wat you'd be right in the middle of

the city and everywhere you turned you would be looking across rice

fields and see rows and rows of timber houses with smoke rising from

them in the morning and the towers of shrines sticking up through the

trees ... it must have been an unbelievably beautiful place."

It's still a beautiful

place -- as the one million tourists who visited Siem Reap and its

Angkor temple-cities in 2012 would no doubt attest.

And hotel and tour operators are predicting a significant increase in tourist arrivals for 2013.

It could be some time

before more of the "lost city" of Mahendraparvata's sites are excavated

and its temples are made more accessible -- there's still much de-mining

to do on the plateau, too.

In the meantime,

however, locals are hoping the new discoveries inspire more travelers to

explore remote sites such as Koh Ker and Beng Mealea, and that the

intrepid will hop on the backs of motorbikes at Mount Kulen.

Getting there

Several airlines fly

directly to Siem Reap in Cambodia and 30-day tourist visas are available

upon arrival for many nationalities for $20. Bring passport photos.

Most visitors employ a local guide or hire a tuk-tuk or bikes to explore the Angkor Archaeological Park (open daily, 5 a.m.-6 p.m.).

An Angkor Pass can be purchased at the entrance gate: one-day $20, three-day $40 and seven-day $60.

ABOUTAsia Travel offers tours of the Angkor cities.

Backyard Travel offers one-day expeditions to Mount Kulen and day trips Koh Ker and Beng Mealea.

HeliStar offers flights over the Angkor cities, including to Mount Kulen and Koh Ker, beginning from $90.

2:40 AM

2:40 AM

specialshowtoday

specialshowtoday

There's nothing like a helicopter

flight over Angkor to provide insight into how vast the ancient city

really is. A new report released by the U.S.-based National Academy of

Sciences has revealed a much grander Angkor landscape than previously

known, one without parallel in the pre-industrial world.

There's nothing like a helicopter

flight over Angkor to provide insight into how vast the ancient city

really is. A new report released by the U.S.-based National Academy of

Sciences has revealed a much grander Angkor landscape than previously

known, one without parallel in the pre-industrial world.

Posted in:

Posted in:

0 comments:

Post a Comment